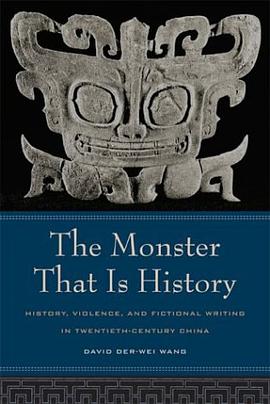

The Monster That Is History

内容简介

In ancient China a monster called Taowu was known for both its vicious nature and its power to see the past and the future. Over the centuries Taowu underwent many incarnations until it became identifiable with history itself. Since the seventeenth century, fictive accounts of history have accommodated themselves to the monstrous nature of Taowu. Moving effortlessly across the entire twentieth-century literary landscape, David Der-wei Wang delineates the many meanings of Chinese violence and its literary manifestations. Taking into account the campaigns of violence and brutality that have rocked generations of Chinese - often in the name of enlightenment, rationality, and utopian plenitude - this book places its arguments along two related axes: history and representation, modernity and monstrosity. Wang considers modern Chinese history as a complex of geopolitical, ethnic, gendered, and personal articulations of bygone and ongoing events. His discussion ranges from the politics of decapitation to the poetics of suicide, and from the typology of hunger and starvation to the technology of crime and punishment.

......(更多)

作者简介

王德威

國立台灣大學外文系畢業,美國威斯康辛大學麥迪遜校區比較文學博士,曾任教於台灣大學及美國哈佛大學,現任哥倫比亞大學東亞系及比較文學研究所教授•著有《從劉鶚悼王禎和:中國現代寫實小說散論》、《眾聲喧嘩:三○年代與八○年代的中國小說》、《閱讀當代小說:台灣、大陸、香港、海外》、《小說中國:晚清到當代的中文小說》、《眾聲喧嘩以後:點評當代中文小說》等書•

......(更多)

目录

......(更多)

读书文摘

Fiction may be able to speak where history has fallen silent.

《对照记》不止刊出张自孩提至暮年的写真,也包括她的父母甚至祖父母的造像。她写道,“他们只静静地躺在我的血液里,等我死的时候再死一次。”

......(更多)